New York, April 21, 2021

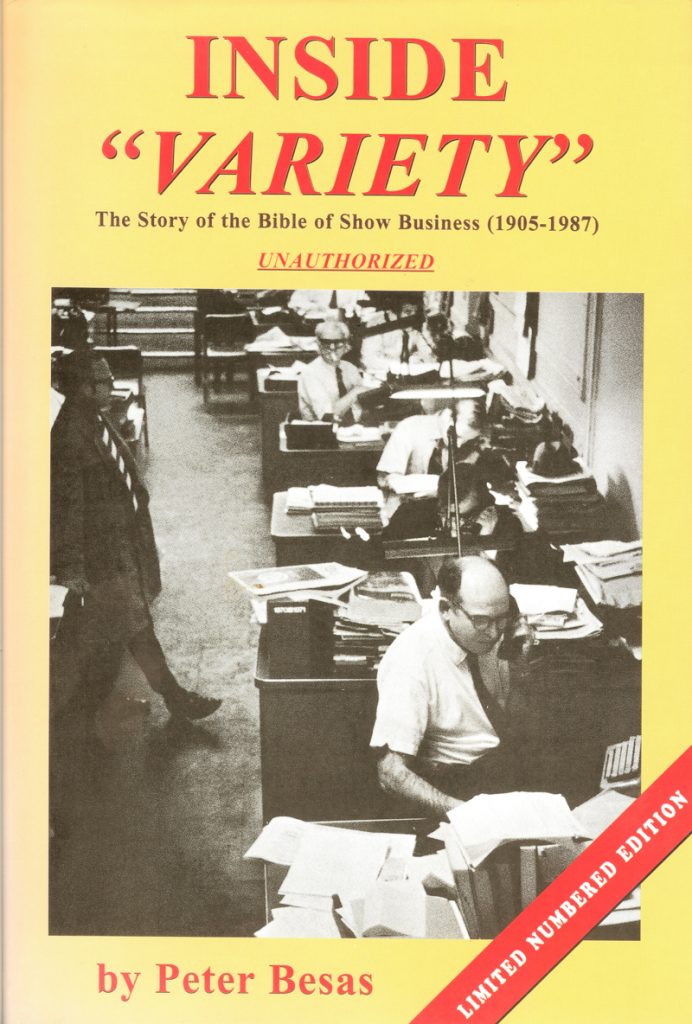

The twisted history of public reporting of U.S./Canada box office—the grosses!—gets a look in a story that cites Variety as the historical pace setter, and quotes muggs Marie Silverman Marich, the late Larry Michie and Peter Besas’ book Inside Variety (Ars Millenii, 2000)

Summary box office has been provided to the press since the mid-1990s, but before that time getting a count of ducats from the wickets was difficult, patchy and inconsistent.

Marie was one of the journos who wrote the “L.A. Box Office” at Daily Variety in the 1980s while Larry wrote the notoriously difficult Washington D.C. box office stories starting in the mid-1960s. Both pieced together raw box office numbers from local theatres to create a mosaic, as was the custom in that era.

Pulling the historical recollection together, Peter’s book Inside Variety recounts the full history, starting with the Bible of Showbiz coaxing figures out of the then-biggest theatre chain in the period around World War I (that goes back to silent films!).

The website MarketingMovies.net, which just published the analysis article, is connected with Robert Marich’s book Marketing to Moviegoers (in three editions). So Bob relied on no-less-an-authority than his wife, Marie, for eyewitness recollections.

Variety just published a story speculating that national box office summaries may go hush-hush again to some degree, since Hollywood has been patchy in reporting to the press during the pandemic.

——-

One little-appreciated outgrowth of the pandemic-related “new normal” is that reporting box office grosses immediately and publicly has become irregular. For about a quarter century previously, industry allowed cinema ticket sales revenue to be publicly announced quickly, though it’s little remembered that previously those figures were confidential (explained further down).

“As Moviegoing Returns, Will Hollywood Studios Continue to Hide Box Office Grosses?” says the headline of an excellent recent Variety story by Rebecca Rubin that raises this specter. What’s happened is that, with cinema depressed during the Covid-19 restrictions, there’s a growing tendency for Hollywood film distributors to keep quiet about box office results for their films. The reason is that Covid-era results paled in comparison to normal times.

“For indie studios, box office reporting has been mixed,” says the Variety article. “Companies, including IFC Films, 101 Studios, and Solstice Studios, have remained transparent. However, Searchlight Pictures, which is owned by Disney, wasn’t originally forthcoming with revenues for Chloé Zhao’s Oscar-frontrunner Nomadland, which played in more than 1,100 theaters. Likewise, indie distributor A24 was quiet with opening weekend ticket sales for Lee Isaac Chung’s drama Minari, another Academy Award hopeful. And Neon didn’t share figures for Billie Eilish: The World’s a Little Blurry’ a documentary about the pop star that debuted simultaneously on Apple TV Plus.”

On the Hollywood industry going quiet recently, Warner Bros. Pictures has been opaque on reporting mediocre box office for Tenet, the offbeat sci-fi film that premiered Sept. 3 domestically. Warner Bros. should get credit for trying to support cinema by releasing PG-13-rated Tenet, which finished with a domestic (U.S. and Canada) cinema gross of $58.4 million; but that’s weak since a total in the hundreds of millions of b.o. dollars was expected in normal times. International b.o. was a healthier $305.2 million for Tenet, as overseas theatres were less impacted by the pandemic at that point.

The Variety article continues: “Other major studios, such as Universal Pictures and its specialty label Focus Features, as well as Disney, have continued to document numbers in a traditional manner during the pandemic,” writes Rubin. “Paramount Pictures hasn’t released any movies in a standard theatrical fashion in the past 12 months, but the company plans to report grosses for A Quiet Place Part II on May 28.”

It remains to be seen if Hollywood film distributors return to the practice of full and prompt disclosure of box office data. It’s worth noting that at best, they’d probably only be able to delay circulation of box office news. That’s because today’s four biggest theatre circuits are all publicly traded and must make disclosures for investors. Those big-four Wall Street-listed theatre chains are Regal Cinemas (part of UK-based Cineworld), AMC Theatres, Cinemark USA and Canada’s Cineplex, as well as some smaller circuits.

Since the middle 1990s, the industry has allowed complete box office summary data to be announced publicly, much like the Nielsen ratings for TV shows. “So in a sense, box office figures are a blessing and a curse for Hollywood”, observes Paul Dergarabedian, senior media analyst at Comscore and cinema industry veteran.

When a film does well at the box office, industry shouts the blessed news, since it’s human nature for the public to latch on to hits. Bad box office has the opposite effect, since the consumers figure low-grossing films are probably snoozers.

“A film that ranks number one in national box office one week can be marketed as ‘America’s most popular movie’ for the next seven days,” says the business/academic book Marketing to Moviegoers: Third Edition. “If a comedy ranks third behind a kids’ film and a fantasy drama in the closely-watched weekend box office, then it can be advertised as ‘America’s number-one comedy!’ as was the case for MGM’s 2010 box office dud Hot Tub Time Machine.”

Another factor in less public reporting is that the video streamers often put the kibosh on reporting box office for their original films’ limited releases in theatres. Reasons aren’t clearly stated but it’s probably because box office isn’t particularly impressive for truncated showings.

From the birth of cinema into the 1980s, there was no official national box office publicly announced, though trade papers published spotty figures. Information became known on an ad hoc and mostly localized basis such as a specific theatre revealing that it set a record for box office or that a film distributor achieved a company record for a given title.

Over the years, Hollywood trade newspapers compiled figures for some key cities, which would identify the winners and losers on a systematic basis, and provided some historical comparisons. At the core, those key cities were New York, Chicago and Los Angeles.

By the early 1990s, overall box office was announced with the blessing of industry. The source was a compiling service with the bland name Entertainment Data Inc., referred to in the trade by its initials. EDI assembled figures that were sold to the trade that provided industry aggregate and granular data; each distributor no longer had to compile its own list by trading figures with competing distributors and theatres.

EDI’s history illustrates how box office reporting was a backwater within living memory. The box office data service was founded in 1976 by Marcy Polier, who worked as an office secretary at a film distribution company. She realized that Hollywood needed to replace the longstanding practice of film companies laboriously calling each other to share figures, and compiling their own box office stats in endless duplication. Polier eventually hired her boss to work for her at EDI (very amicably!) and then sold the data company for $26 million; that’s a startling price tag given it simply pulled together not-so-secret information (the successor to EDI is Comscore).

What was it like to run the numbers in that pre-disclosure era? The writer of this article turns to his wife for an authoritative explanation, because it was she who assembled and wrote the Los Angeles box office stories for Variety in the 1980s.

When serving as assistant West Coast editor for Variety, Marie Silverman Marich recalls that she’d receive a 5-inch stack of paper with raw weekend box office figures on Sundays and Mondays that were the basis of L.A. box office stories covering weekends. That blizzard of paper detailed every play date for over 100 theatres within 50 miles of Los Angeles.

“It was the type of job where you’d use a ruler to go down the sheets of paper to keep the endless rows of numbers straight,” Marie recalls. “It was very time-consuming and fully manual. It took two full days of each week to compile the ‘LA Box Office,’ The task involved adding up ticket sales from every screening of each film of interest, from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off to Full Metal Jacket to Risky Business, a film that certified Tom Cruise’s star power.

Variety’s ticket-sales guru in that era was the late Art Murphy who pioneered modern box office reporting and was a recognized source for cinema figures and insights. In those days, the Variety office relied on manual typewriters, analog adding machines with paper ribbons and carbon paper (usually surrounded by ash trays overflowing with cigarette butts!). Many people thought Murphy simply stored all the numbers in his head.

Getting personal again, this scribe can well recall how, just a few decades ago, cinema box office results were unobtainable on a rapid and comprehensive basis. While he was a media reporter at Investor’s Business Daily in the mid-1980s, the paper began publishing Friday-through-Sunday national box office figures for peak holiday weekend in its printed Tuesday edition.

Receiving weekend box office figures early Tuesday morning, as recently as the mid 1980s, was a revelation for Wall Street analysts in New York who previously had to piece together anecdotal information. Surprisingly, well-heeled financial executives would comb trade newspapers for snippets of information and rely on personal Hollywood contacts, or otherwise wait days for print trade publications to arrive at their offices. Electronic information transmission was in its infancy.

This early publication of box office in the 1980s by Investor’s Business Daily provided such tidbits as that Paramount Pictures had landed a surprise hit with an inexpensive Australian pickup Crocodile Dundee — which grossed a then-astounding $174.8 million domestically to rank second in revenue for the year. Box office information for films of indie film company Carolco Pictures (the Rambo pics, Terminator 2: Judgment Day and Basic Instinct) was particularly prized in that era; Carolco’s share price was dependent on its film performance since it was a medium-sized company.

Those early not-announced national box office days seem a million years ago, but are within living memory. Those outside the small circle of cinemas and distributors may find that the era of underground box office data may return in some fashion.

The History of Box Office Reporting As Seen Through Variety

The book Inside Variety by Peter Besas (Ars Millenii, 2000) recounts how news coverage of box office “remained spotty and unsystematic” for most of the prior century. Only in the past 25 years have complete film performance summaries been made public. The book chronicles the evolution of b.o. reporting by the New York-based trade paper.

“As early as the 1920s weekly Variety was regularly sending a reporter to the office of Sam Katz, head of the Publix theatre circuit, then the largest in the country, who provided Variety with a list of film grosses in New York and other major cities,” says Inside Variety.”

The spotty, ad hoc coverage was consolidated in the 1940s and systemized as the film business grew in sophistication. Local box office for 24 cities became regular news in the pages of Variety, with more context and historical comparisons.

Along the way, the Inside Variety book says film distributors tried to hype results to make their films look better while exhibitors downplayed them, hoping to wiggle out of paying fair rentals to film distributors. “I don’t believe anyone in the whole industry ever thought anyone ever told the truth”, commented the late TV reporter Larry Michie, when he was gathering b.o. data fot the Weekly in Washington in the 1960’s..

By 1969, Variety established enough consistency to introduce a “top 50 films” chart — a favorite of readers because the information was vital and previously unavailable. Variety journalists did their best to cross-check stats with sources, so figures were believed to be generally accurate though not precise. In these early days, compiling cinema ticket revenue stats involved more than simply accepting figures provided by industry.

In 1976, box office compiler Entertainment Data Inc. began confidentially compiling and archiving data, gradually providing the press with more and more top-line figures, meaning a summary. By the 1990s, EDI figures on top-line revenue for each film were made public enabling the press and public accurate information on a daily basis. The wealth of granular data underneath the summary is purchased by industry, and is not available for mass public consumption.

End