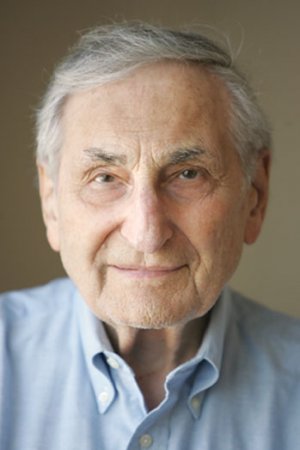

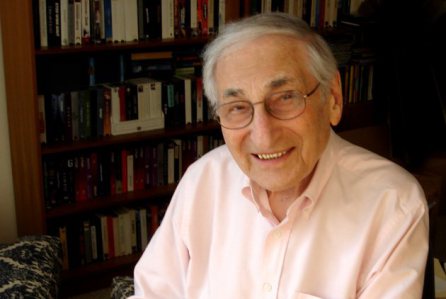

Veteran mugg Hy Hollinger, a gentle soul and the antithesis of the pushy reporter, passed away, aged 97, last Wednesday (Oct.7) at the Olympia Medical Center, Los Angeles. Hy had been retired since 2008 after chronicling show biz history as a journalist and helping shape it when working on the studio/industry side.

In a storied career as a journalist, Hy Hollinger held senior editorial posts at Variety and Daily Variety in two stints for a total of 20 years, from 1953 to 1960 and 1979 to 1992, where he was among the paper’s most knowledgeable and unflappable muggs. He finished his career at The Hollywood Reporter (1992-2008) after being unceremoniously axed during the Cahner’s regime under Peter Bart. One day when he came into the Daily’s office on Wilshire Boulevard he was suddenly told to “clear out his desk” and was escorted to the door. Hy thereupon started legal proceedings against the company for age discrimination and eventually obtained a settlement.

In the course of his long career, Hy held jobs in publicity at Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros. He had a front-row seat to unfolding Hollywood history while based in New York, Los Angeles and London.

After his first Variety stint Hy joined Paramount but this time as an executive, as he commented on a previously-posted item on Simesite. First he was publicity director of International Telemeter Co., an experimental pay-TV operation. He later became European Production Publicity Director based in London, then ad-pub vice-president.

When in film publicity, Hy worked on Paramount’s Love Story and other films of the 1960s and 1970s. After a management change at Paramount, he transitioned to corporate public relations with clients that included the National Basketball Players Assn. and Sagittarius Productions,which was owned by Seagram chief, Edgar Bronfman.

Hollinger leaves many imprints on the modern media/entertainment business from his work in journalism. It can be said that he was a driving force in the creation of the American Film Market. In the 1970 and 1980s while a journalist at Variety Hollinger reported on the discontent of independent Hollywood film sellers with prices being charged and services provided by the French for the Americans’ marketing operations when they set up shop during the Cannes Film Festival. These sales companies eventually launched the American Film Market in 1981 in Los Angeles as well as the associated non-profit film trade group now known as the Independent Film & Television Alliance (IFTA).

While based in London for Variety and working for London bureau chief Don Groves, Hollinger helped develop a ground-breaking system for tracking revenue generated by films in the patchwork of overseas theatres. At the time, international box office was largely not covered by journalists due to the difficulty in obtaining and evaluating data. Hy also was The Hollywood Reporter’s overseas box office guru in the 1990s and 2000s in the final phase of his career.

During the 1980 Cannes Festival, Hollinger broke the story in Variety that the festival jury, chaired by Kirk Douglas, was blind-sided by a decision made unilaterally by festival organizers to elevate a French film to co-winner status. The film was announced as winning the “Grand Prize of the Jury” when actually it had been passed over by the jury.

In the best Variety tradition, despite rubbing elbows with the rich, famous and powerful, Hollinger was not awed by Hollywood glitter and maintained a down-to-earth personality that reflected his roots. Born Herman Hollinger in the Bronx, Hollinger was the son of Jewish immigrants – Max from Rumania and Minnie from Poland. His father was in the fur business and his mother a housewife. Hy was educated at Townsend Harris High School, the City College of New York and the Columbia University School of Journalism.

Hy’s first newspaper job from 1932-1935 was at the New York Times, working on Saturdays during high school as a copy boy and messenger in the classified ad department. While attending Columbia’s Journalism School, Hy landed a job as a CBS Radio intern working the 1940 Republican convention… rubbing shoulders with such CBS stars of the era as Robert Trout, John Charles Daly and political analyst Elmer Davis.

During World War II, Hy served mostly overseas from 1942-45 as a sergeant in Armed Forces Radio. Afterwards, he worked for a suburban Philadelphia weekly, then covered sports for the now-defunct New York Morning Telegraph and eventually moved to Warner Bros. as a publicist.

“Hy was particularly adept at getting major studio box-office figures — both foreign and domestic,” said former THR business editor Robert Marich. “His contacts on international box office were great and a source of mystery.

“To me, Hy was the best of trade reporters at the time. He was approachable and personable, but not a patsy. He could not be bought. He’d seen it all and was unflappable.”

As Hollinger once recalled, he was walking in midtown Manhattan when he had a chance encounter with his former Variety boss Syd Silverman and Variety executive Robert Hawkins. That led to him returning to the weekly in 1979 as an associate editor based in Hollywood, to cover “all aspects of show business with special emphasis on the international scene.”

In 2012, Hollinger wrote about an assignment for Warner Bros. when, as a young publicist, he was told to escort Les Brown Orchestra singer Doris Day — who had just signed a contract with the studio — to the Daily News Building in Manhattan for a photo shoot to publicize her first movie, 1948’s Romance on the High Seas.

“The News photo editor said he needed a Christmas cover shot for the magazine section and sent me off to Brooks Costume to rent a Santa Claus outfit,” Hollinger wrote. “Little did I know I would be the fall guy, but there I was as Santa bestowing a gift on Doris Day. That photo was seen by millions. Wonder if it’s still in the News archives?”

Hollinger was pre-deceased by his wife of 61 years, actress Gina Collens, who died in 2014. He is survived by his daughter Alicia, who is a digital artist and writer living in Los Angeles.

The above was compiled mostly by Frank Segers and Bob Marich, with Hy’s collaboration. A few additional items were added by Peter Besas.

———–

On the occasion of the printing of the Souvenir Album for the 100th Anniversary celebration of the founding of Variety by Sime Silverman, held in Sardi’s Restaurant in New York in 2005, PB asked a number of muggs to contribute articles for the Album. The following was sent in by Hy Hollinger and included in the Album:

The Daily Grind on 46th St.

What I remember most about my early days on Variety at West 46th Street was the undisciplined routine and atmosphere. There were no assignments, only beats. Nobody told you when to come in or when to leave. You only had three news-gathering days, Thursday, Friday and Monday. You spent Tuesdays at the printing plant reading proofs and playing poker. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday were days off. You were required to turn in a ton of copy by Monday night.

The new edition of the Weekly was passed around on Thursday and each reporter was asked to write his four-letter signature on the stories he contributed. It was suggested that it would be better to write the stories as soon as you picked them up. Nobody paid attention. I remember Herb Golden, Gene Arneel and me (and later Fred Hift and Vince Canby) pounding on our Underwoods to 2 a.m. to meet our deadlines as Monday turned to Tuesday.

And if you were a dedicated mugg, which most staffers at the time seemed to be, you had a key to the office and could drop by Saturday or Sunday if you wanted to avoid the Monday night typeathon.

Oh, I forgot: there were assignments for reviews. Posted Thursday morning on the guard rail protecting Abel’s balcony perch. Your extracurricular reviewing responsibilities could be a movie, a radio show, a nitery, a book, a vaudeville show, a new act, legit theatre or, believe it or not, an opera at the Met. Sometimes you got lucky when Abel had something else to do. You could wind up with a supper club at one of the posh hotels, a great asset during your dating days.

As a new mugg starting out on 46th Street, your fixed assignment, at least until a new hire joined the staff, was reviewing the weekly vaudeville show at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem every Friday night, a formidable task for a novice. In doing my homework by reading hundreds of past reviews in Variety archives, I came across the word “ofay”, which I subsequently used to show off my sophisticated command of Variety “slanguage” to describe a white act that occasionally appeared on the all-Negro (now Afro-American) bill. I learned the origin of the word “ofay” at one time, but memory now fails me what it meant. All I could find in my current Webster’s New World: “ofay”: slang, a white person; a term of disparagement or contempt.”

Broadway was the center of the entertainment universe. Hollywood was only a factory town.The headquarters of all the major studios were a short walk from West 46th Street. Reporters on studiio beats covered them from head to toe, investigating every aspect of financial distribution, legal, and ad-pub activities, and sometimes getting barred from their buildings if they probed too hard.

MGM’s publicity department was set up like a newspaper city room. Many of the film flacks were former newspapermen and wrote books between their extolling duties. One Christmas gift from MGM was a book of short stories from the trade press contact. The big boss of the department was a noted Broadway moonlighter, ad-pub vp, Howard Dietz, who kept a piano in his office where he and Arthur Schwartz worked on musical reviews, with Dietz providing the lyrics to Schwartz’s melodies. They’re best known for Dancing in the Dark, also the title of a first-class memoir by Dietz.

At smalltown Broadway you could run into showbiz people anywhere. It was not uncommon for Abel to flag you down at Lindy’s, wave you over to his table, and introduce you to Groucho Marx or some other luminary. My initial four-letter signature was Holl. But it some way found its way to Ron Holloway when I left the paper. When I returned years later, it became Hyho thanks to Bob Landry.

Hyho

end