Madrid, October 8, 2019

Since there are ever fewer and fewer postings on the Simesite as the months and years slip by, in order to show that the Site is not utterly comatose, we have decided to post excerpts from Variety’s Souvenir Album once a month which we feel former muggs might appreciate re-reading.

The Album was printed back in 2005 on the occasion of the 100th Anniversary celebration of the founding of Variety in 1905 by Sime Silverman and was held during a gala dinner in Sardi’s restaurant in New York.

Sadly, most of those who contributed articles to the Album have now passed away, so it is a fitting tribute to their memory to “rescue” these articles and reminiscences from the past which were included in the Album.

We have previously posted four contributions sent for the Souvenir Album by muggs Keith Keller, Larry Michie, Hy Hollinger and one on Jimmy Durante and Sime. You can read all these by scrolling down the

pages.

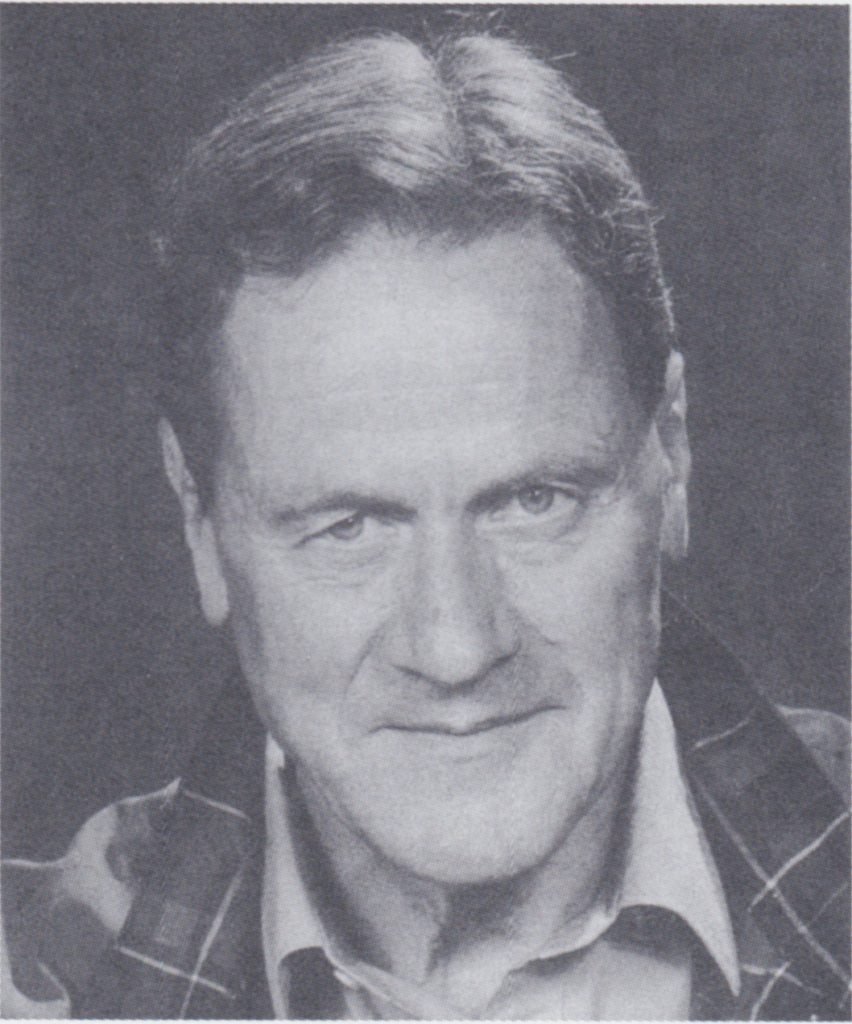

For the fifth installment, here is one penned by Besa concerning his recollection of an encounter with LA sales supremo, Hal Scott.

REMEMBERING “MR HOLLYWOOD”, HAL SCOTT

“Mr Hollywood” is what many called Hal Scott and the monicker seemed an appropriate one for Weekly Variety’s top salesman on the Coast. The first time I visited Los Angeles around 1976 on a sales trip for the Latin American issue, and not knowing a soul in the big city, it was Hal I called from my hotel in Beverly Hills around 9 p.m. He was already asleep, but we met the next day and he graciously showed my wife and me around on a kind of mini-tour and took us out for dinner.

Hal, whom I had first met at Cannes, was tall, debonaire, every bit of what I imagined to be an Angeleno. As a salesman he was alternately smooth and commanding. Of course, he was handling the prime territory in the world for Variety, and while the likes of me was happy to sell a quarter of a page ad to some small company in Spain, Hal would sell spreads and dozens of pages to his clients, which ranged from the schlockmasters to some of the studios.

So when I approached him about contacting some of my Hispanic clients in LA I did so with a degree of trepidation, half expecting he wouldn’t even bother to contact them. But Hal followed up every lead I gave him, and a few ads came trickling in for the Latin issue.

One of Hal’s great talents, as with all good salesmen, was schmoozing. Not only with clients, but with other muggs. When he came to Europe, even though he was not of the expatriate stripe like most of us, he nonetheless seemed to fit in and despite his dapper attire and the rumored Rolls Royce that he drove in Hollywood, and his California style, he became “one of the family”. He was doubtless somewhat puzzled about the way the “hybrids” abroad ran their operations, but he always joined in the fun in Cannes and lived life to the hilt.

My favorite story of Hal’s was one he told me when I interviewed him for my book Inside Variety. It was what he called his ”worst selling experience”. He had just gotten the job as salesman with Variety in 1949, at $65 a week, and he saw that Mae West was going to make a comeback and open at the Sahara Hotel in Vegas. Checking his rate card, he saw that the front cover of weekly Variety was selling for $5,000, a huge sum in those days. He makes his pitch, and Mae West goes for it. She’ll take the ad!

So he calls up New York ad speaks to Murray Rann, the ad manager. “I sold the front page!” “What do you mean you sold it?” says Rann. “Mae West is gonna take it,” says Hal. And Rann replies, “We don’t sell the front page.” “But it’s on the rate card!” Hal pleads. “I don’t care what’s on the rate card. We don’t sell the front page!” Upon Hal insisting, Rann spoke to Harold Erichs, the business manager at that time. But the answer was still “no”.

Hal called back Mae West and urged her to take the back cover instead. She answered,”Mr Scortt, you told me there was only one place fir me and that was on the front page. If I can’t have that, I don’t want anything.” Commented Hal at the end of the interview with me, “There were no deals of any kind at Variety. No discounts. I mean, we were holier than thou. We were the Bible of show business!”

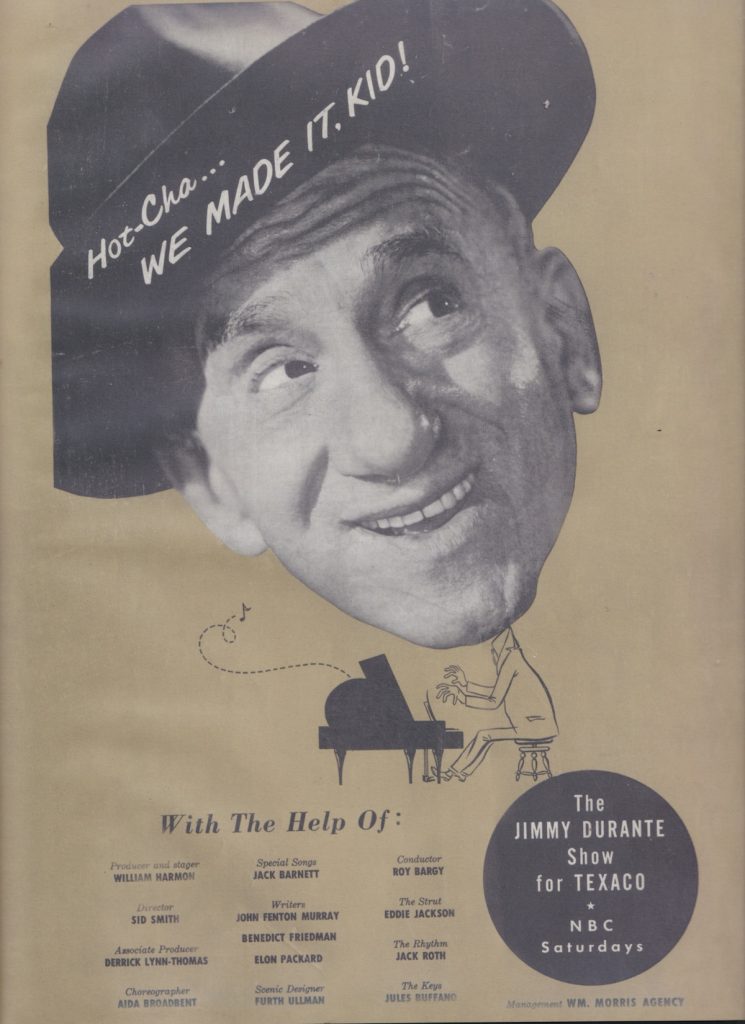

DURANTE AND SIME

It started – the lifelong at times eccentric friendship between Sime Silverman and Jimmy Durante – in an ofay Harlem joint known as the Club Alamo. The speakeasy-nitery was an infrequent wayside stop in the nocturnal wanderings of Variety’s founder-publisher-editor and while Schnoz doesn’t quite remember now the exact night in the early ‘20’s when he first came to Sime’s attention, and vice-versa, he does recall that they “reached” each other quickly.

That first time, Sime asked that Jimmy be brought to his table. Schnoz was fracturing a piano with a New Orleans jazz combo at the Alamo. Also in the show, but not then Durante’s partner, was the strutting Eddie Jackson. In those days it was general policy for the performers to mingle with the guests and the request for the piano player to sit and chin with the sandy-haired bow-tied Sime, with whom he was otherwise thoroughly unfamiliar, was then a matter of course.

From then on, Sime “made” the Alamo more and more frequently, strongly attracted by Durante and the rowdy pianistic humor. Jimmy recalls that Sime sometimes brought with him some of the Variety boys, particularly Jack Conway and/or Johnny O’Connor. The Schnoz says Sime would hold plenty of conversation with him every time he came up to the Alamo, but Jimmy isn’t quite sure now regarding just what he taught Sime. He does remember though, that Sime often expressed confidence the Schnoz would “get there”.

The friendship between Sime and Schnoz more fully ripened a few years later when Jimmy, “the Well-Dressed Man”, but no businessman, opened the Club Durant (no final “e”) on Broadway in partnership with Eddie Jackson. Harry Harris, a singer, and Frank Nolan, a waiter at the Club Nightingale, a joint that preceded the Alamo on Durante’s speakeasy circuit. The Club Durant didn’t tee off like a financial ball of fire; rather the Schnoz admits, if it wasn’t for Sime and his free-and-easy spending style the joint would have closed in the first few weeks.

Lou Clayton, a crackerjack hoofer who had just split with Sammy White, entered Jimmy’s life about three months after the Club Durant opened. Clayton, an aggressive and knowledgeable Broadway habitué, bought out Harris’ interest in the joint and thus one of the most famous of show biz combos – Clayton, Jackson & Durante – came into being. Sime made them famous all over the world; first with a series of comic stories in Variety; secondly with sage “management” (sans commission, of course); third, by inspiring a number of the comedy highlights of the Clayton, Jackson & Durante night club routines…

By 1950, Clayton, Jackson & Durante played their first theatre date as a trio – at Loew’s State on Broadway. They didn’t exactly flop, but they certainly weren’t a hit. Sime, according to the Schnoz, took their so-so reception as a vaudeville act like a personal affront.

A year later, Schnoz and his partners were booked into the Palace. They were then also playing at the Silver Slipper, and that’s where they rehearsed their stage act in the early morning hours.

A week before their Palace opening, Sime showed up at the Silver Slipper with Jimmy Hussey, the late and great Gaelic with the Yiddish dialect. It was 4 a.m. Sime watched the boys rehearse. The Schnoz was singing what he figured to be the act’s opening: “I Can Do Without Broadway, but Can Broadway Do Without me?”

Sime said: “If that’s going to be your opening, you can bet money Broadway will be able to do without you!” Durante recalls that Sime then took off his coat and worked with them for hours, routining their act as he visualized it to be right for the Palace. They were a big hit.

—-

For those too young to remember: Jimmy Durante was known as “Schnoz” due to his large Cyrano-like nose, about which he often kidded with audiences. He was famous not only for “fracturing” the piano, but also the English language. The “I Can Do Without Broadway” song became one of the top hits of the decade. The “Palace”, on Broadway, right near the Variety office, was the legendary theatre for anyone in vaudeville. To have “played the Palace” meant you were in the “big time”. “Jimmy, the Well-Dressed Man” was another of Durante’s big hits, the joke being that he was anything but well-dressed. “Ofay” is not a typo. It was a term used to indicate white audiences in Harlem. Joe Schoenfeld, the author of the above article, was a reporter in the Weekly and was then made editor-in-chief of Daily Variety in 1950. PB

THE DAILY GRIND ON 46TH STREET

What I remember most about my early days on Variety at West 46th Street was the undisciplined routine and atmosphere. There were no assignments, only beats. Nobody told you when to come in or when to leave. You only had three news-gathering days, Thursday, Friday and Monday. You spent Tuesdays at the printing plant reading proofs and playing poker. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday were days off. You were required to turn in a ton of copy by Monday night.

The new edition of the Weekly was passed around on Thursdays and each reporter was asked to write his four-letter “signature” on the stories he contributed. It was suggested that it would be better to write the stories as soon as you picked them up. Nobody paid attention. I remember Herb Golden, Gene Arneel and me (and later Fred Hift and Vince Canby) pounding on our Underwoods to 2 a.m. to meet our deadlines as Monday turned to Tuesday.

And if you were a dedicated mugg, which most staffers at the time seemed to be, you had a key to the office and could drop by Saturday or Sunday if you wanted to avoid the Monday night typeathon.

Oh, I forgot there were assignments for reviews, posted Thursday morning on the guard rail protecting Abel’s balcony perch. Your extracurricular reviewing responsibilities could be a movie, a radio show, a nitery, a book, a vaudeville show, a new act, legit theatre or, believe it or not, an opera at the Met. Sometimes you got lucky when Abel had something else to do. You could wind up with a supper club at one of the posh hotels, a great asset during your dating days.

As a new mugg starting out on 46th Street, your fixed assignment, at least until a new hire joined the staff, was reviewing the weekly vaudeville show at the Apollo Theatre in Harlem every Friday night, a formidable task for a novice. In doing my homework by reading hundreds of past reviews in Variety archives, I came across the word “ofay”, which I subsequently used to show off my sophisticated command of Variety “slanguage” to describe a white act that occasionally appeared on the all-Negro (now Afro-American) bill. I learned the origin of the word “ofay” at one time, but memory now fails me what it meant. All I could find in my current Webster’s New World: “ofay, slang, a white person; a term of disparagement or contempt.”

Broadway was the center of the entertainment universe. Hollywood was only a factory town .The headquarters of all the major studios were a short walk from West 46th Street. Reporters on studio beats covered them from head to toe, investigating every aspect of financial, distribution, legal, and ad-pub activities, and sometimes getting barred from their buildings if they probed too hard.

MGM’s publicity department was set up like a newspaper city room. Many of the film flacks were former newspapermen who wrote books between their extolling duties. One Christmas gift from MGM was a book of short stories from the trade press contact. The big boss of the department was a noted Broadway moonlighter, ad-pub vp, Howard Dietz, who kept a piano in his office where he and Arthur Schwarz worked on musical revues, with Dietz providing the lyrics to Schwarz’s melodies. They’re best known for Dancing in the Dark, also the title of a first-class memoir by Dietz.

At smalltown Broadway you could run into showbiz people anywhere. It was not uncommon for the legendary editor Abel Green to flag you down at Lindy’s, wave you over to his table, and introduce you to Groucho Marx or some other luminary. My initial four-letter “signature” was Holl, but it some way found its way to Ron Holloway (the Berlin correspondent) when I temporarily left the paper. When I returned years later, it became Hyho thanks to Bob Landry, who had become editor-in-chief after Abel’s death.

end

A TV TIPPLER IN A GIN FACTORY

Covering a beat for Variety a few decades ago was like being a tippler let loose in a gin factory.

In my case, I was given a pretty good seat in the theatre that was Washington D.C. in the 1960s. It was a scary time, but a lot of fun, and I was eager to get to work every day. We didn’t have computers or even fax machines—everything went to New York by telex, then we ran the same tape off to L.A. I got to go to the White House, Capitol Hill and everywhere else in town. The hours were long and the pay was low, but if I had any money I would have paid to do the job.

One of my favorite memories from those times has a certain resonance, given corporate shenanigans that regularly emerge on the front page these days.

In 1966 International Telephone & Telegraph had offered to buy ABC, which at that point was financially marginal. Leonard Goldenson, the head of ABC, and his number two man, Si Siegal, had dolled up the television network to make it appealing. They finally expanded the ABC evening news program from 15 minutes to half an hour. CBS had been first, in 1963, with Walter Cronkite interviewing President Kennedy during the inaugural telecast, and NBC had been quick to follow. To bolster its attempt to compete in the evening news and seem big-league, ABC hired a Canadian kid named Peter Jennings as anchor. Good looking, excellent voice, but he flopped badly. End of career (ho-ho).

There was a great deal of concern on Capitoll Hill and throughout the consumer watchdog community that ITT might corrupt the news/political/corporate world by taking over a television network, and an outspoken pot-smoking New Age member of the FCC, Nicholas Johnson, helped lead the opposition. Now that all three of those original networks and their various media spawn are owned by mega corporations the controversy may seem a tad quaint, although there are loads of folks today who think the ITT nightmare came true, and in spades, with the current dominance of GE, Disney and Viacom. To say nothing of Time-Warner.

Well, there were FCC hearings and the stock swap – big for those days, but Wall Street chump change now – was approved, but a court appeal resulted in more FCC hearings in 1967, and finally, in 1968, ITT called off the merger/buyout amid a flurry of platitudes.

I believe I was present when the words were spoken that ended the deal, and they had nothing to do with the platitudes or the legal battle.

It was during the 1967 round of FCC hearings in the old Post Office building on Pennsylvania Avenue, just a short walk from the National Press Building, where Variety had its D.C. office. Si Siegal was being interrogated under oath in a roomful of ITT and ABC lawyers and executives, FCC officials and reporters. The questioner was trying to put Siegal on the spot, and he brought up the value of the stock that Siegal, Goldenson and other shareholders would receive in exchange for transferring ownership to ITT.

The interrogator said, Just how did you arrive at this value for selling the company to ITT? Siegal gave a shy, self-congratulatory smile, ducking his head like an embarrassed little kid. Well, he said, we would have taken a lot less.

The moment passed unremarked during the hearing, and the deal was pending for some time after that, but I thought that was the moment the merger was called off. How could those ITT folks, who had been bragging about what a good deal they’d made, go back to the board and the other stockholders and explain how they’d paid too much. Poor old Si Siegal should have said, We hoped to get a lot more but they drove a hard bargain and we had to settle for what we could get. That might have saved the merger. That was my theory, anyway.

That story played out over years, as was true with such perennial front-page-worthy yarns as copyright legislation, cigarette advertising on television, political pressures on network programs, and so forth. While those great saga were unfolding, there were other striking outbursts of news nearly every week. The pleasure was not just in the events themselves, but in the fact that every word I wrote was going to appear in Variety, including analysis, opinion, wisecracks and pontification. Variety definitely wasn’t a wire-service kind of publication with just the facts, m’am. We delighted and outraged readers every week; poor Syd and the other editors were constantly on the phone listening to industry executives demand that one mugg or another be fired (I’m proud to say I was the target a few times), and disgruntled insiders were always calling us to plant stories, true or not, that discredited their bosses or rivals. What a funhouse! And by the way, a lot of sound, original, valuable reporting got done.

That was the good thing about being a reporter – the sheer, rakehell joy of being able to stick your nose in where it’s not welcome.

But there’s a harsh penalty paid by a reporter as well. Your mistakes are always right there in type. You can’t claim you didn’t write it. There it is on the page. Your flaws are humiliating. Every time you file a story you’re asking for trouble. Your mistakes are boldly presented in black and white.

Fortunately, as my wife and closest friend know, I never made any.

end

Our first contribution, sent by Keith Keller, our former Copenhagen correspondent. One day as I was chatting with him in Cannes he mentioned the mouse story to me. I had never heard it before. But before he could tell me the story, he rushed off to some film screening. He subsequently submitted the following story to me for inclusion in the Souvenir Album.

NORMA AND THE MOUSE

Being late for a date with Syd’s – and before that, Abel Green’s – secretary, Norma Nannini, just wouldn’t do on my first trip to New York as the new Danish Bureau chief for Variety back in 1979. Even though I was actually all of two months her senior at Variety when in 1956 we were both hired for minor positions at the paper.

I had called Norma from Lower Manhattan. Working for Variety in those days was Heaven on Earth, especially when compared to the assignments given me by my local Danish paper, BT, where I was expected to rush through my interviews in 24 hours on trips to New York and then hurry back to JFK.

It must have been the spring or fall of 1979 when I had that morning appointment. I was on a private holiday trip on a cheapo Iberia flight and hoped very much to see Syd Silverman and other “top executives” of Variety in the flesh. I had advised Norma about all of this in a letter more than a week earlier and repeated it in an ultra-brief phone call from JFK right after I landed. I wasn’t quite prepared for her response.

“Mr. Keller? On what matter are you calling Variety? Mr., uh, Keller, was it?”

“Miss Nannini,” I blurted out.” I had never believed the day would come when I would finally get to see you face to face. You remember we agreed on my coming to see Syd Silverman and yourself around 11 a.m., if you could arrange that… You have already set up the appointment? Great! My sincere thanks! But I first need instructions on how to find you. I’m presently lost in a maze of downtown alleyways, somewhere near Battery Park, on Carlisle Street, at a friend’s house.”

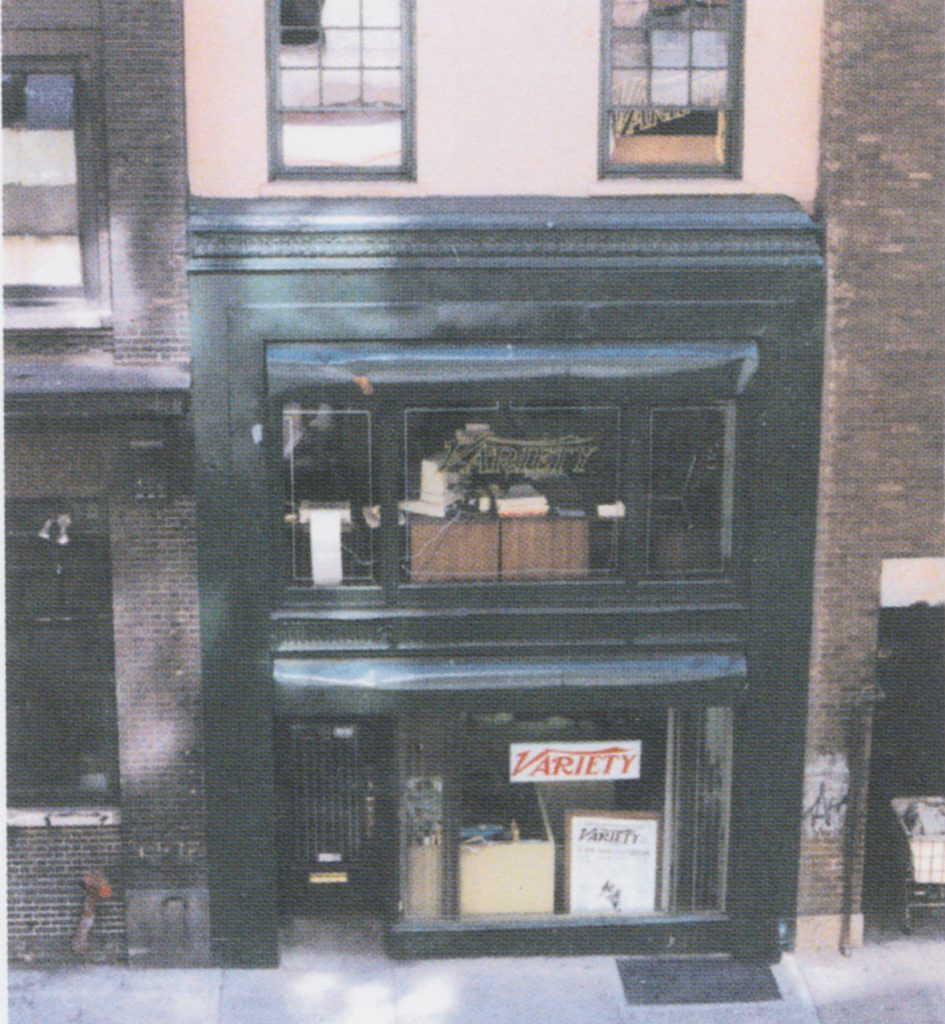

The instructions were forthcoming. Next morning at 9:50 a.m. I found myself in front of the locked door of Rosie O’Grady’s Restaurant & Pub, a favorite pre-show rendezvous place. There was a slight drizzle as I stood looking at the bronze back of George M. Cohan on Times Square. Finally, after killing an hour, I strode eastwards on 46th Street, but could at first see no building resembling what I imagined to be the world headquarters of the renowned Bible of Show Business.

I presently stopped before Number 154. If I hadn’t seen the Variety logo on the window, I might have taken it for some sort of machinery repair shop. Was there maybe a doorbell? There were several, one for each floor. I started with the second floor, and almost right away I heard the rapid thudding of sneakers coming downstairs, three steps at a time, ending with one long silent jump and there was Chris Higgins standing before me, holding the literature section of the New York Times under his left arm and almost tearing the door off its hinges with his right.

“Mr. Keller?” he said, flashing a smile as bright as a spotlight. “Miss Norma is waiting for you.”

We shook hands briefly, then he turned and waved me ahead. I followed him up the steep stairs, passing the “holy ground” of the second floor editorial department, which i had heard about from descriptions of staffers I had met in Cannes and elsewhere. On the third floor Chris gave the door facing the hallway two firm knocks, opened it slightly, and did a disappearing act.

I gently pushed the door a little further open, until it wouldn’t budge anymore. It was as though a large piece of furniture, maybe a leather armchair, were blocking it. I remember thinking that this was where Raymond Chandler would have revealed that the obstacle was a stiff. But I did finally squeeze into the room, and was confronted with two huge towers of back issues of the IFN. (International Film Number) The room was large, but looked smaller because there were shelves covering every available inch of wall space. They were stacked with more newspapers, magazines and a seemingly innumerable number of boxes, each marked in neat, tiny handwriting, as well as piles of books of all sizes, all looking untouched in their dusty wrappers. I then noticed a huge table, piled high with mountains of letters in red and green, IN and OUT boxes, and a humungous litter of pamphlets, press releases and junk mail.

In this massive debris, something or somebody was moving. Some body part. A woman, wiggling and breathing hard.

“For Pete’s sake! Help me! Lift the goddamn table top!!”

“How on earth did you get there?” I asked against my better judgment.

“None of your business… I was trying to get hold of my mouse-trap! There’s a mouse in it! It’s all kind of splattered and bloody.”

“Why don’t you call Chris Higgins?”

“Didn’t you hear me? GET…ME…OUT!”

And that is what I did, as best I could. I had never even seen Norma’s face, let alone her full figure. The whole scene was weird. Our bodies rudely mashed together; if only sideways, our breathing was loud and out of sync, the darkness in front of us nearly total.

Norma was evidently trying to bend further forward to the left, still groping for her ghastly object, while I risked unpredictable injuries to my knees and spinal column by hunching my back against the desk’s underside and succeeded in lifting the table just the eighth of an inch or so for Norma to move herself backwards with her mousetrap.Very slowly I eased myself out from under the table and maneuvered into an upright position. I bent again – to dust my knees — then felt sufficiently restored to finally face Norma Nannini. Only there was no Norma to face. She had slipped out of the room.

A few seconds later, the door opened and a dark-haired lady of medium height and weight, in her 30’s, stepped into the room and stretched out a well-manicured hand towards me and said with a smile so radiant that it could have lit up all of Madison Square Garden: “I’m sorry to have kept you waiting, Mr. Keller. Or do I call you Keith?”

After our brief but firm handshake, she pointed to a comfortable chair for me to sit in. She herself walked around the desk of our recent encounter and sat down and started to arrange one of the piles of papers. She then launched into a monologue about how the whole building was gradually collapsing and that rats and vermin would follow the mice, and that the whole Times Square area was doomed to be replaced by high rise buildings.

I managed to duck out of the room after a few minutes and descended to the swinging doors on the second floor editorial section and headed up the steps of the editorial dais. A small crowd was clamoring to get Syd Silverman’s or Bob Landry’s attention. Syd caught sight of me, and gave me a mute sign about being with me in a moment. Suddenly I was slapped first on one, then the other shoulder by a middle-aged man with bright friendly eyes and glasses hanging down to the tip of his nose.

“You must be our new Viking mugg!” he said.”Welcome aboard the vessel of alternative harmony and disagreement.”

Kell